Brother and Sister Looking Forward to Living Together

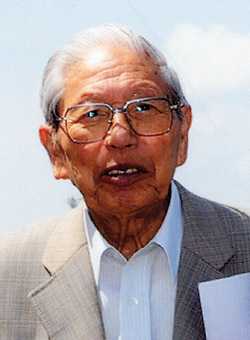

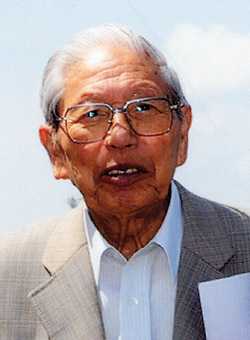

Takeo Ueharada

The Ueharada family lived in Takajo-machi (now, Honkawa-cho, Naka-ku). Takeo Ueharada’s father Yoichi (then, 50) experienced the atomic bombing while working at the court of appeal, which was located in Ko-machi, approximately 500m from the hypocenter. He died on August 13. Takeo’s mother Chiyoko (then, 40) and younger sister Sumie (then, 16) were also exposed to the bomb when, as part of the Volunteer Citizen Corp, they were helping with building demolition in Zakoba-cho (now, Kokutaiji-machi 1-chome, Naka-ku) approximately 900m from the hypocenter. Chiyoko was trapped under a concrete wall and died. Sumie could only see Chiyoko’s lower arm; there was nothing that she could do to help. All Sumie could do was put her hands together in prayer for Chiyoko and run through the flames. Takeo’s younger brother Masayoshi (then, 12) and younger sister Yoshie (then, 9) are still missing.

Takeo was demobilized from the military and came back from Iwate Prefecture on August 19 to live with his younger sister Sumie. To make ends meet, he arranged for her to live with relatives in Kabe while he entered the police school. The brother and sister were looking forward to living together soon, but Sumie started to lose her hair. Her chronic fatigue evolved into a high fever. She passed away in her brother’s care on June 28, 1946. Having lost all five members of his family to the atomic bomb, Takeo was left alone. He spoke of his sad experiences only to his wife and children. However, 52 years after the bombing, he felt, “I must tell people how horrific atomic bombings and wars are, and how important peace is. Innocent people who have done nothing wrong should not have to suffer from prejudice or discrimination because they are A-bomb survivors. It is a painful thing to do, but I must communicate and tell people the truth.” He soon spoke about his A-bomb experience on a television program.

Courtesy of Takeo Ueharada

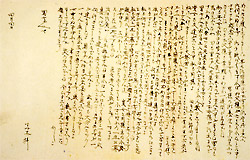

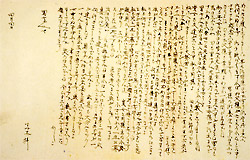

Draft of letters from Sumie to friends

These are drafts of letters that Sumie wrote in 1946.

In the letters she describes how, on the day of the bombing, she joined her hands in prayer for her mother, who she was unable to save as she was trapped under a concrete wall, how she was unable to rest, even though she was unwell, as she was staying in her relatives’ home, and how she was looking forward to living together with Takeo. However, as there was no stamp fee these letters were never sent to her friends.

Donated by Takeo Ueharada

Mushroom Club

Radiation caused by the atomic bomb affected babies in the womb. There were many stillbirths, and those who made it into this world had higher mortality rates compared with unexposed children. When mothers in early stages of pregnancy were exposed to radiation near the hypocenter, their children were sometimes born with an extremely small head (a syndrome called microcephaly), sometimes associated with intellectual disabilities. These children required special care just to manage daily life.

Parents who had children with microcephaly did not learn for nearly 20 years that there were others suffering from the same condition. As there were people who wrongly thought that A-bomb survivors were likely to give birth to disabled children, they tended to isolate themselves, unable to share their suffering with anyone.

Research efforts by the Hiroshima Research Group founded by author Tomoe Yamashiro and others shed light on the lives of microcephaly patients and their families. As a result, in 1965 an association of microcephaly patients and their parents was formed. The name of this association, Mushroom Club, represents the wishes of the parents for these lives born under the mushroom cloud. They may be living in the shade now, but they will grow and emerge with strength from beneath the fallen leaves, just like mushrooms.

The Mushroom Club continued to call on the government to help microcephaly patients, and in 1967 the government admitted the relationship between microcephaly and the atomic bomb. Today, there are 22 A-bomb microcephaly patients in Japan recognized by the government.

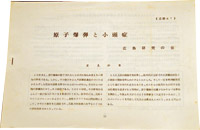

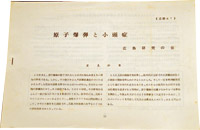

The Atomic Bomb and Microcephaly

Hiroshima Research Group used extracts from papers announced by ABCC (Atomic Bomb Casualty Commission) and Hiroshima University, and identified the medically proven correlation between A-bomb radiation and microcephaly. The ABCC paper was the first to be published in 1952. These papers were not known by the general public until 1965.

Entrusted to Hiroshima University Archives

The Hatanaka Family

The Hatanaka family are always together. Yuriko used to spend the day in the barber shop run by her parents.

July 1973 Taken by Masahiko Shigeta

On August 6, 1945, Yoshie Hatanaka was three months into her pregnancy. She was exposed to the atomic bomb in Nishi-daiku-machi (now, Eno-machi, Naka-ku) approximately 800m from the hypocenter. Numerous pieces of glass pierced her body, and she was drenched by the black rain. Yoshie hovered between life and death, suffering from acute radiation symptoms such as hair loss and vomiting of blood. When her husband Kunizo came back from the war, the Hatanaka family moved to Otake Town (now, Otake City). The couple ran a barber shop, and in 1946, Yoshie gave birth to Yuriko. Yuriko had microcephaly and was not able to walk even after turning three. She needed special care to help her with daily life and was unable to go to school.

In 1965, Kunizo joined Mushroom Club and became the club’s first chairperson. In 1978, Yoshie, who always said, “I cannot go and leave Yuriko alone,” died of cancer. Kunizo died in 2008. Yuriko is now a part of her younger sister’s family.

The Okada Family

Yoshikazu Okada, who joined the coming-of-age ceremony from Miyazaki Prefecture. They were very much looking forward to meeting everyone from Mushroom Club.

January 1966 Taken by Masahiko Shigeta

A clothing shop owner Kazuichi Okada and his wife Tame were struck by the atomic bomb in their house located in Ebisu-cho, approximately 860m from the hypocenter. Their house was completely destroyed, so the couple moved to Tame’s parents’ home in Miyazaki. Tame suffered from A-bomb sickness but gave birth to Yoshikazu in 1946. Yoshikazu was an extremely small baby, which made Tame worry about whether or not he would grow healthily. The Okada family moved back to Hiroshima to reopen a clothing store, but that did not work out well. They returned to Miyazaki and started a general store.

At age 4, Yoshikazu started kindergarten, but the teacher told Tame that Yoshikazu seemed intellectually handicapped compared with ordinary children. Tame felt like it was the end of the world.

Yoshikazu started at elementary school, but he could not keep up with the other students. Kazuichi initiated a movement calling for the Board of Education and schools to provide special classs (called ‘special-needs classes’ today, referring to classes for children with disabilities). When Yoshikazu was in the 4th grade, a special class was established. As a result of Kazuichi’s lobbying efforts, the junior high school also set up a special class. Yoshikazu entered 2 years after children his age, but he did graduate.

In 1963, Kazuichi died of cancer. To worsen her suffering, their store was completely burned down by a fire that spread from the house next door. Tame, despite her A-bomb illness, which forced her to spend almost half of each month in bed, restored her store to support her life with Yoshikazu.

Around 1983, Tame had a stroke that left her partially paralyzed. Still, she kept saying, “I cannot die and leave Yoshikazu alone.” She committed herself to rehabilitation to regain her physical functions. Later, Yoshikazu was admitted to a different hospital that had artificial dialysis equipment due to acute renal failure. Tame and Yoshikazu were always in each other’s minds, though they were in distant hospitals. In May 1998, Yoshikazu died, followed two months later by Tame.