Life of Endurance

The Hiroshima Peace Memorial City Construction Law, established in 1949, got the recovery of Hiroshima City off the ground. However, issues of compensation and support for A-bomb survivors long remained unaddressed. People who were mentally or physically injured by the A-bombing could not reveal their grief. Though suffering from the loss of family or anxieties about their own health and prospects, they were unable to call for help.

Loneliness and Anxiety

To protect children who had lost their parents in the A-bombing, Hiroshima City established a reception center for war orphans in Hijiyama within two days after the A-bombing. Afterward, facilities newly established by Hiroshima Prefecture, individuals and religious groups, as well as facilities restored from war damage, received children. They were managed with support from Japan and abroad. Some survivors were aging, with increasing anxiety for health and life, as well as losing their children and emotional support. The first A-bomb survivors nursing home, “Funairi Mutsumien,” opened in 1970, 25 years after the A-bombing.

|

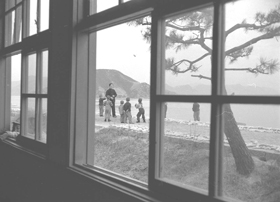

Children of “Ninoshima Gakuen”1952 Ninoshima IslandIn 1946, the Ninoshima Gakuen for Hiroshima Prefecture War Orphans was established at the former site of the Ninoshima Quarantine Station. Ninoshima Gakuen housed, fostered and provided guidance to children who had lost their blood relatives. |

|||

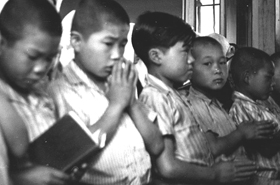

Children of “Hikarinosono”1949 Moto-machiIn April 1948, the nuns who had provided shelter and care for children with no relatives opened “Hikarinosono—House of Setsuri” in Moto-machi. |

|

|||

An old man visiting the Tokasan Festival1954 Mikawa-choThis old man lost his sight in his left eye, as well as his family in the A-bombing. Seeking lively places frequented by many people, he visited the Tokasan Summer Festival. |

An old lady using a crutch1951 Nishi-hiratsuka-choAn old lady, living alone, prepares a meal outside, her gradually-weakening body supported by a crutch. |

Injured Minds and Bodies

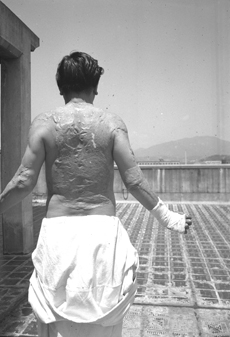

The A-bombing left deep scars on both the minds and bodies of A-bomb survivors. In addition to the suffering from burn marks and keloids, A-bomb survivors hesitated to seek employment, get married or have children because groundless rumors that A-bomb diseases were infectious, and/or hereditary aroused anxieties and prejudices. Asymptomatic A-bomb survivors also had to combat anxieties about suddenly developing aftereffects of A-bomb radiation. A special medical facility for A-bomb survivors, Hiroshima Atomic Bomb Hospital, was established in 1956.

Girls playing in the river1952 Motoyasugawa RiverThese girls had fun digging sand at the riverside. One of them was digging with only her left hand, because she couldn’t stretch her right arm due to scar tissue from burns. |

Back of “A-bomb Victim No. 1”(Left)1949 Senda-machi 1-chomeKiyoshi Kikkawa showed his keloids, revealing appalling injuries from the A-bombing, and was called “A-bomb Victim No. 1” by the U.S. press. He was hospitalized in the Hiroshima Red Cross Hospital until April 1951. After that, he dedicated himself to establishing A-bomb victims’ organizations as well as peace campaigns. |

||

A woman in a summer dress1953 In front of Hiroshima StationThis woman’s left arm shows a painful burn mark. Some people wore long-sleeved clothes all year round in order to conceal their scars and burn marks. |

|||